Sarah Keeley has been in charge of ECMWF’s numerical weather prediction (NWP) training programme since 2011.

Her research on a wide range of topics in meteorology and climatology has given her the breadth and the depth of expertise required for the job.

This year’s series of NWP training events at ECMWF has just started with two courses on the assimilation of weather observations into forecasting systems, a process referred to as data assimilation.

Other courses to follow later this year cover topics such as the numerical methods used in NWP, predictability and ensemble forecasting, and the modelling of small-scale physical processes in the atmosphere.

Diverse interests

Dr Keeley’s interest in meteorology goes back to her teenage years. But, like many of her colleagues in ECMWF’s Research Department, she did not initially train as a meteorologist. Instead, she obtained a degree in physics at the University of Oxford and specialised in atmospheric physics in her final year.

Her PhD at the University of Reading was in climate science, exploring how human-induced climate change might affect weather regimes.

Dr Keeley currently works on the representation of sea ice in ECMWF’s Integrated Forecasting System. (Photo: Thinkstock/Mike Watson Images)

Subsequent research projects were devoted to modelling the ozone hole and its impact on Antarctic climate and to improving seasonal weather forecasting.

“I’ve changed fields each time I changed jobs, moving from the very long timescales involved in climate studies to the shorter timescales of NWP, and working my way from the top of the atmosphere to the ocean surface,” Dr Keeley says.

Today, as a scientist in ECMWF’s Research Department, she spends two thirds of her time working on the representation of sea ice in ECMWF’s Integrated Forecasting System (IFS), while the rest of her time is taken up by her role as the Centre’s Educational Officer.

“The wide range of my research interests has helped me gain the kind of overview which has proved invaluable to my training role,” she says.

Supporting Member States

Participants in ECMWF’s training courses range from forecasters and researchers in meteorological services in the Centre’s Member and Co-operating States to postgraduate researchers at universities across the world.

“We often find that their academic background may be in maths or physics without specific knowledge of NWP,” Dr Keeley says. “We provide a very quick way to get them up to speed.”

The provision of training for the benefit of Member States is part of ECMWF’s official duties, and participants from those states are given priority access to the training programme.

Sarah Keeley became the Centre’s Educational Officer in 2011. As a member of the Earth System Modelling Section in the Research Department, she is working on the implementation of a sea ice model in the forecasting system.

ECMWF’s Convention, which came into force on 1 November 1975, says one of the Centre’s objectives is to “assist in advanced training for the scientific staff of the Member States in the field of numerical weather forecasting”.

“We want to inspire them”

The training covers the full range of topics in numerical weather prediction and is delivered by ECMWF experts working in the respective fields.

“What they teach goes all the way to the cutting edge of their work. We don’t just want to teach the participants the basics, we want to inspire them,” Dr Keeley says.

“One of the things the participants really value is the chance to interact with the Centre’s staff.”

The training used to be provided in a block of several weeks, but the trend has been towards shorter courses and for participants to pick and choose which ones they wish to attend.

“This year all our courses have gone to a one-week format in response to requests from Member States,” Dr Keeley says.

The data assimilation course has been split into two parts: a general course on ‘Data assimilation’, including on the mathematical techniques involved in combining observations with short-range forecasts, and a EUMETSAT-funded course on ‘Satellite data assimilation’.

The course on the ‘Parametrization of subgrid physical processes’ covers ‘moist processes’, including convection and clouds. (Photo: Thinkstock/Creatas Images)

The course on ‘Advanced numerical methods for Earth-system modelling’ looks at how to solve the equations that describe atmospheric flow efficiently on supercomputers, looking at what is done currently as well as potential future methods on new supercomputing hardware.

Small-scale processes, such as radiation and land surface effects and convection and clouds, are the subject of the course on the ‘Parametrization of subgrid physical processes’.

Finally, the course on ‘Predictability and ocean-atmosphere ensemble forecasting’ looks into the predictability of the atmosphere in the medium and extended range, and into ways to create a probabilistic forecast system and its verification.

Coupled processes

In addition to her training role, Dr Keeley works as a scientist in the Research Department, where she is part of the Coupled Processes Group in the Earth System Modelling Section.

She is currently working on implementing a dynamic sea ice model in the forecasting system.

“It’s part of the ocean model and has been included in an ocean reanalysis, ORAS5, which is currently in production. But it has not yet been activated in the operational forecasting system.”

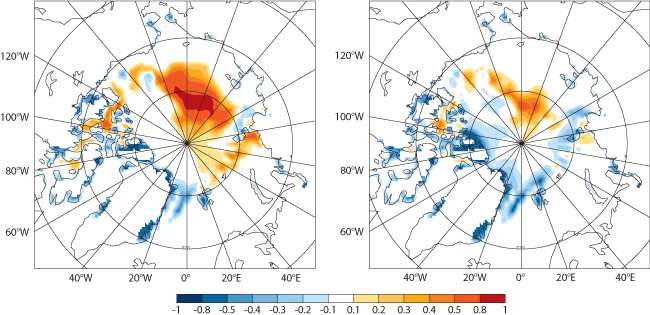

Errors in the prediction of sea ice fields are much smaller when a dynamic sea ice model is used. The charts show the difference between sea ice concentration observations (from satellite estimates) and a 32-day forecast for 2 September 2007 using a static sea ice model based on the 2002–2006 climatology (left) and using a dynamic sea ice model (right).

Others in the Coupled Processes Group work on different parts of the Earth system, such as waves and the land surface.

“We’re trying to get the different parts of the model to talk to each other, while capturing the key coupled processes that are important on a range of time scales,” Dr Keeley explains.

Her dual role as ECMWF’s Educational Officer and a scientist working on model development means her career prospects are wide open.

After all, the Centre’s first Educational Officer from 1979 to 1982, Erland Källén, went on to become Professor of Dynamic Meteorology at Stockholm University and is now the Director of ECMWF’s Research Department.