Claudia Di Napoli, Scientist, Forecast Department

When I am asked how my summer went, the first image I picture in my mind is my car thermometer stuck at 29°C at midnight shortly after I landed in Italy. It was the third week of July and the beginning of a heatwave that would grip Southern Europe for the days to come. A second heatwave hit shortly before I flew back to the UK at the end of August, as if to mark the end of my stay in the same way as the beginning.

Now that meteorological autumn has started, I look back and see how summer 2023 did not fall short of scorching conditions and impacts associated with extreme heat.

Heat and health

A heatwave is a period when high temperatures, lack of ventilation (i.e. very little or no wind), intense insolation and often high humidity coincide to establish abnormally hot weather.

During a heatwave, human health may be at risk. Extreme heat can overwhelm the human body's ability to cool down its inner temperature during the day, leading to dehydration, heat exhaustion and, in the worst cases, heatstroke. High night-time temperatures can be as detrimental because they prevent the body from recovering from the heat experienced in the daytime. Children, the elderly and people with long-term health conditions, such as diabetes and heart problems, are more vulnerable to sustained heat and related illnesses.

In my previous role as research fellow at ‘The Lancet Countdown: Tracking Progress on Health and Climate Change’ initiative, I also learnt that heat affects health by limiting people's capacity to work and exercise outdoors. As the frequency, intensity, and duration of heatwaves has increased in the past 40 years, so has the number of those potentially exposed to the detrimental effects of heat.

The close connection between heat and health explains why increased numbers of deaths and cases of heart attacks are observed shortly after the onset of a heatwave. Preliminary data show that during the July heatwave, excess deaths among the elderly were recorded in Spain, Italy and France. The press also reported multiple cases of heatstroke in Southern Europe.

July 2023 heatwave

So how hot was summer 2023? Since 2020, ECMWF has been producing a historical dataset of heat stress based on the ERA5 reanalysis. The dataset, called ERA5-HEAT, spans back to the 1940s and provides a gridded record of the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI). UTCI estimates the heat build up in the human body due to air temperature, wind speed, water vapour pressure and short‐ and long‐wave radiant fluxes. Such a build up is called heat stress.

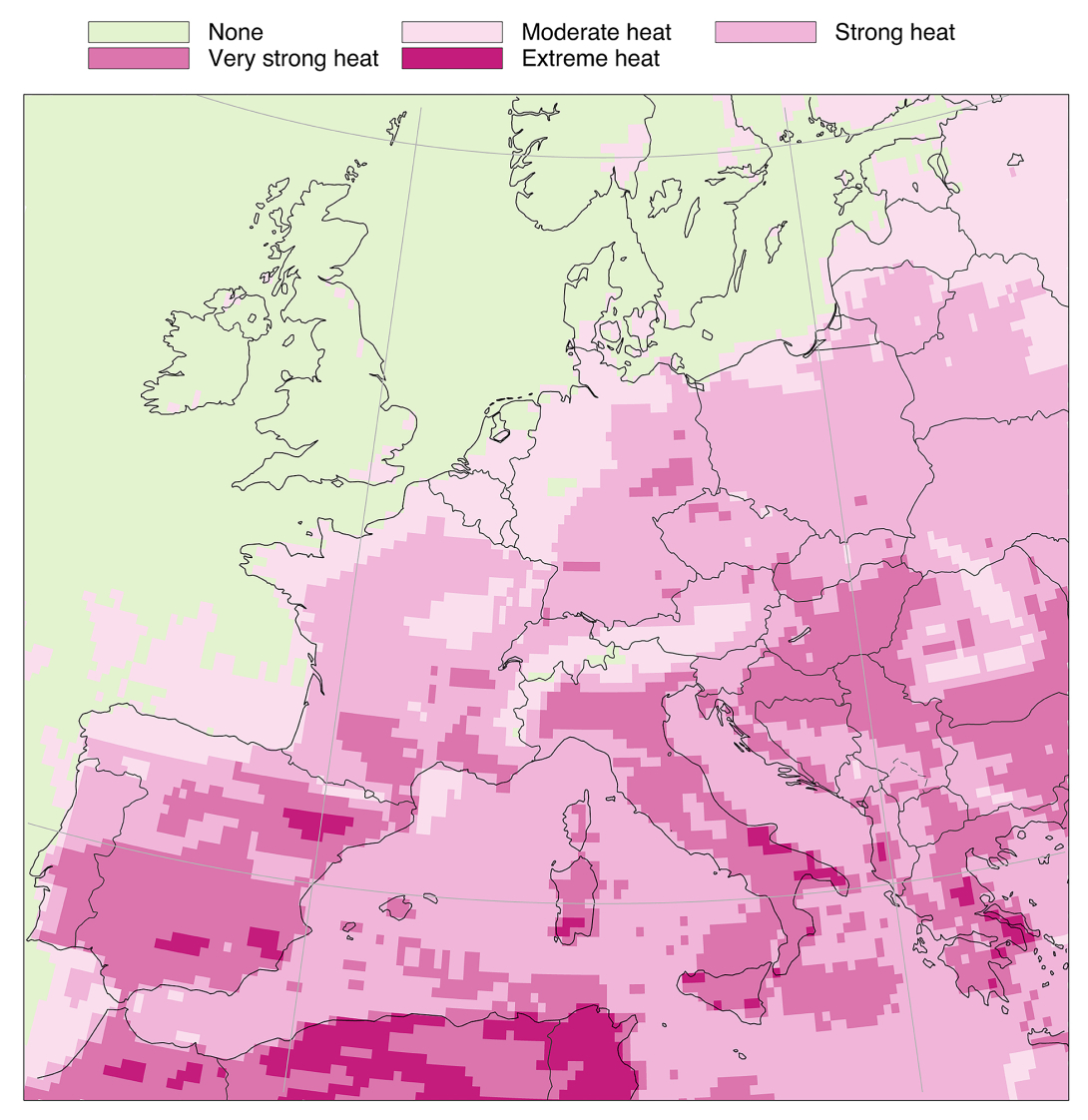

For the July 2023 European heatwave, ERA5-HEAT shows widespread conditions of heat stress across the Mediterranean, reaching extremely high levels in some areas of Spain, Italy and Greece. These levels are indicative of a potentially hazardous health/heat environment where it is imperative to cool yourself down immediately and take actions to avoid heatstroke.

Heat stress during the July 2023 heatwave. The map shows locations where the highest conditions of heat stress occurred between 15 and 27 July 2023 in Europe (as represented by UTCI reanalysis data).

Further, the heatwave followed a period when parts of southern Europe had been experiencing some days of very strong to extreme heat stress since the beginning of the summer, exacerbating pre-existing hot conditions. My colleagues and I talked in more detail about the heat levels preceding the heatwave in a previous blog post.

Bridging the gap

As part of my role at ECMWF, I am leading the development of a prototype information system for weather-related health hazards. Using ECMWF forecasts, the prototype will ultimately generate and disseminate information about upcoming health hazards via state-of-the-art climate and weather indicators, including heat stress indicators such as the UTCI.

My work is part of the EU Destination Earth initiative and the Horizon Europe project TRIGGER (SoluTions foR mItiGatinG climate-induced hEalth thReats), which aims to integrate the prototype with personal exposure monitoring data, thus translating 'what is the weather like?' to 'how does the weather make you feel?'. For this translation to happen, I find it pivotal to understand more about how heat stress indicators would be used in practice.

I am using ECMWF data to develop and test forecasts of the UTCI, looking up to 46 days ahead. The forecasts will be shared with our TRIGGER project partners and through five Climate-Health Connection (CHC) Labs within the five European cities of Augsburg (Germany), Bologna (Italy), Geneva (Switzerland), Heraklion (Greece), and Oulu (Finland).

The CHC labs bring together TRIGGER project partners and stakeholders, such as hospitals and local authorities, who will provide vital feedback on the potential on-the-ground use of the prototype.

Medics in hospitals, for instance, will be receiving the prototype forecasts in a variety of forms while recording the impact of extreme heat events on hospital admissions, as well as the extent to which people being affected have any pre-existing medical conditions. This sort of data can help to inform how the prediction of any upcoming hazardous hot conditions might be targeted for those most at risk.

Working with practitioners in this way will allow me to explore a whole range of questions. For example, how does heat stress predicted through UTCI translate into real-world health issues? What kind of lead times do different sectors need and how can they respond if an event similar to the 2023 July heatwave is predicted? What is the best way to communicate heat stress forecasts?

Addressing these (and many other) questions will help us move towards an operational heat stress forecasting system at ECMWF – a key aim of the work.

I believe that heatwaves such as those that characterised summer 2023 highlight the links between heat stress and human health, and the need for meteorologically-driven knowledge that is able to capture and predict the effect of extreme weather on our wellbeing.

Such knowledge is key in predicting what the weather can do to human health, thus helping society adapt to the growing extremes of climate change.

Acknowledgements

The TRIGGER project has received funding from the European Union under grant agreement nº 101057739.

Destination Earth is a European Union funded initiative and is implemented by ECMWF, ESA, and EUMETSAT. Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them.

Top banner image: kpoppie/iStock/Getty Images Plus